Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.The colour mauve

Nick Thorne traces the Perkin family from apprentice leatherworkers in the 18th century to top scientists in the 20th

In 1856 an 18-year-old Royal College of Chemistry student was experimenting at home in the holidays. His professor, August Wilhelm von Hofmann, had published a hypothesis on how it might be possible to synthesise quinine, an expensive natural substance that was in high demand for the treatment of malaria, from coal-tar. Hofmann, who was intrigued by the coal-tar that was a waste product of making gas, had spotted the ability of his young student and made him one of his assistants just the year before. The boy, William Henry Perkin, had entered the prestigious educational establishment, now part of Imperial College, when he was only 15 years old. Perkin was one of seven children of a successful carpenter and builder from the east end of London who had hoped that his son would become an architect but was prepared to fund his son’s scientific education.

William’s experiment was an attempt to prove his professor’s theory, trying to synthesise quinine from aniline, a coal-tar product. It didn’t work as hoped. Instead he noticed that the cloth which he used to wipe down the bench of the black sludge residue when tidying up produced a purple stain – which would lead to his fortune.

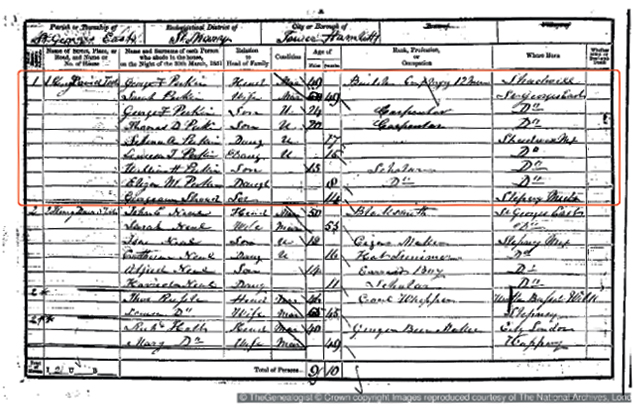

In order to research William’s family story, we can turn to TheGenealogist’s census collection to find where they lived in the years just before he went to the Royal College of Chemistry at a precocious age. The 1851 census of St George’s East in Tower Hamlets, reveals the 13-year-old scholar at number 1 King David Fort. The household is headed up by his father, George, a builder employing 12 men. This was at a time when there was a demand for new terraced houses for dock workers in the surrounding area which could well have been the source of his income. Ten years earlier, in the 1841 count, the family had been living in nearby King David Lane, though the census does not give us the house number.

Where is King David Fort?

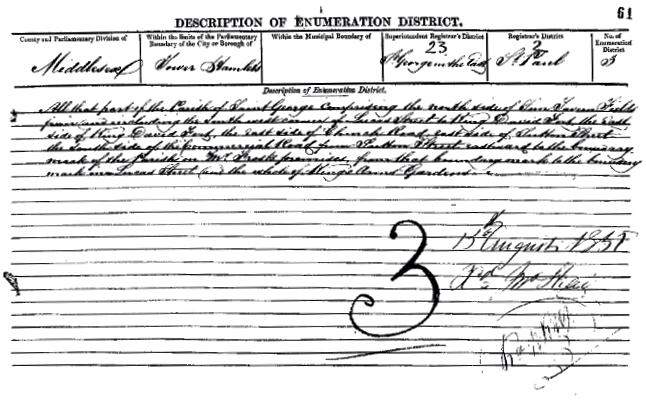

But where exactly is this road called ‘King David Fort’ where the young William discovered the first aniline dye? It is in an area that has changed a lot. By using the back button on the census image window which opened on TheGenealogist, we can navigate to the ‘Description of Enumeration District’ and see it was near Commercial Road – this puts it into the context of its area.

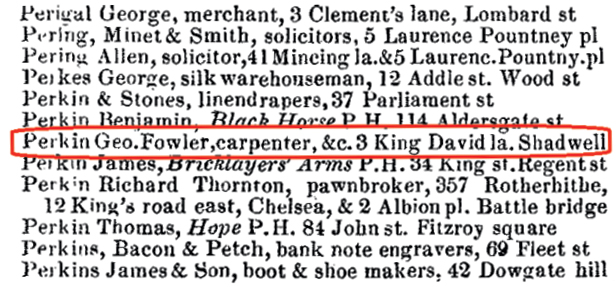

A search of the Post Office Directory for 1846 in the Trade, Residential & Telephone records on TheGenealogist reveals the building number where Geo. Fowler Perkin and family were living: 3 King David Lane, Shadwell. This road was separately enumerated in the census and so we know that the family had moved a short distance between 1846 and 1851 to King David Fort.

By 1856 the Commercial Directory lists George as a builder at King David Fort.

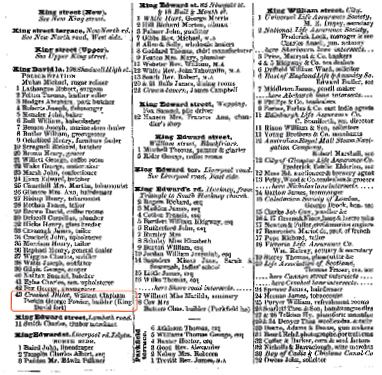

The street index pages of the Post Office Directory gives us the entry for all the heads of households in King David Lane and this ends with the Perkin’s entry including King David Fort in brackets. Today there is a blue plaque to commemorate William’s discovery on the wall of Gosling House, Cable Street across the road near the junction with King David Lane.

By the time of the next census, in 1861, William has married Jemima Harriet Lissett and his occupation has now been established as a scientific chemist. The couple have been joined by the first of their sons, William Henry Perkin Jr. There would be another born that year, Arthur George, but the boy’s mother would die the very next year in the last quarter of 1862. We can use the Birth, Marriages and Death indexes on TheGenealogist to find these vital events as well as their father taking a second wife, Alexandrine Mollwo, in 1866. The boys would gain a half-brother and four half-sisters in the next few years.

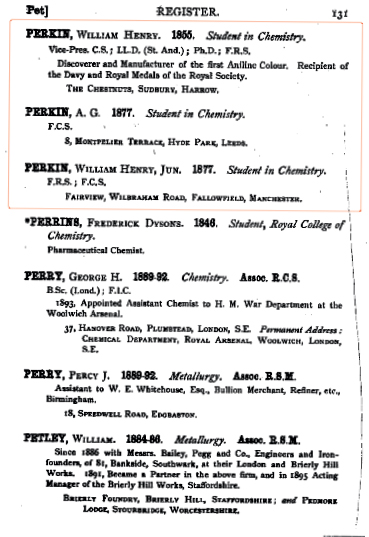

What is noteworthy about the family is that all three boys would become chemists themselves. A search of the Educational records on TheGenealogist finds the Royal College of Chemistry Register in which father and his first two sons appear together on the same page.

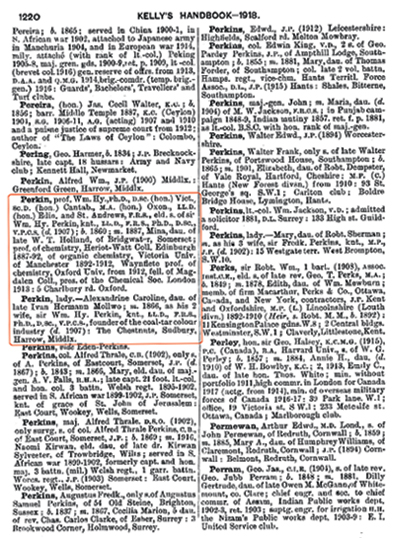

An entry in Kelly’s Handbook to the Titled Landed and Official Classes 1918 from the Peerage Gentry & Royalty records on TheGenealogist points to just how accomplished the eldest son was. William Perkin Junior became a professor of organic chemistry at Heriot-Watt college in Edinburgh in 1887. He then moved to Victoria University in Manchester for the period between 1892 and 1912. From there he proceeded to be the Waynflete professor of chemistry at Oxford, a fellow of Magdalen College and president of the Chemical Society.

William Perkin. Scanned photograph from FJ Moore’s book, A History of Chemistry (Popular Science Monthly Volume 69, 1918)

1851 census on TheGenealogist with William Perkin aged 13 in Tower Hamlets

Royal College of Chemistry Register in TheGenealogist’s education records

The Description of Enumeration District page in the 1851 census on TheGenealogist

London 1846 P O Directory - George Fowler Perkin Carpenter etc

George Fowler Perkin, Builder, in the Commercial Directory 1856

Kelly’s Handbook to the Titled Landed and Official Classes 1918 from Peerage Gentry & Royalty

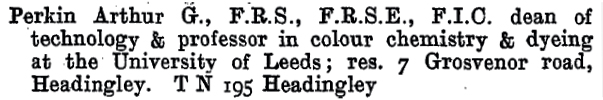

Professor Arthur Perkin, the second son, in Leeds Alphabetical Directory 1923

One professor in the family was not enough

One professor in the family was not enough for the Perkins. A search for Arthur Perkin finds an entry in the Leeds Alphabetical Directory 1923 that reveals he had become the dean of technology and professor in colour chemistry & dyeing at the University of Leeds.

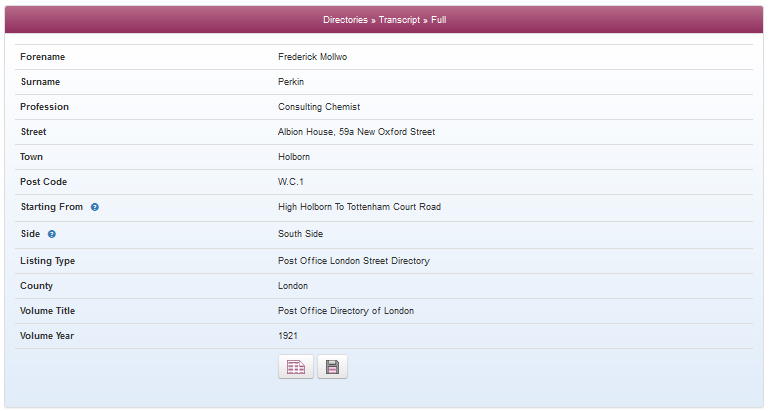

Meanwhile, the two professors’ halfbrother, Frederick, can be found in TheGenealogist’s 1921 census substitute. From this we can read that the younger brother’s profession is as a consulting chemist at 59a New Oxford Street in London.

The father and first son also get entries into the Concise Dictionary of National Biography 1901-1930. The passage that details William Perkin Senior tells us that he was knighted in 1906 and points us to the family having opened a chemical factory on the Grand Junction Canal at Greenford Green.

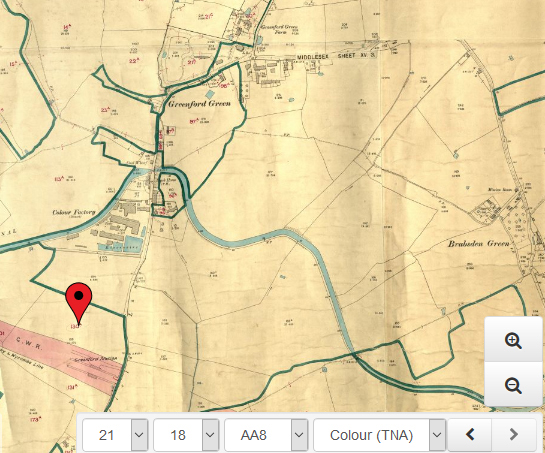

Using the National Tithe Collection on TheGenealogist we are able to find the dyeing factory in Greenford Green on one of the colour tithe maps of Middlesex for an altered apportionment from 1909. By that stage the ‘Colour factory’ is marked as disused on the plan – much of the surrounding fields, however, is still in the ownership of Sir William Perkin and rented out to others.

Returning to records of George Perkin, the builder and father of Sir William, we can see that by 1861 George and two of his daughters were visiting Hastings in Surrey on census night. His occupation is of interest to us as he is no longer recorded as a builder, or even a carpenter as he is now a principal of a chemical works. This points to him providing the capital that his son required to commercially exploit the discovery of the aniline dye. William Snr was joined by his older brother, Thomas, in the new business and so by the 1871 census we find that Thomas, who had been a carpenter at the time of the 1851 population count, was now enumerated as a chemical manufacturer employing 80 men.

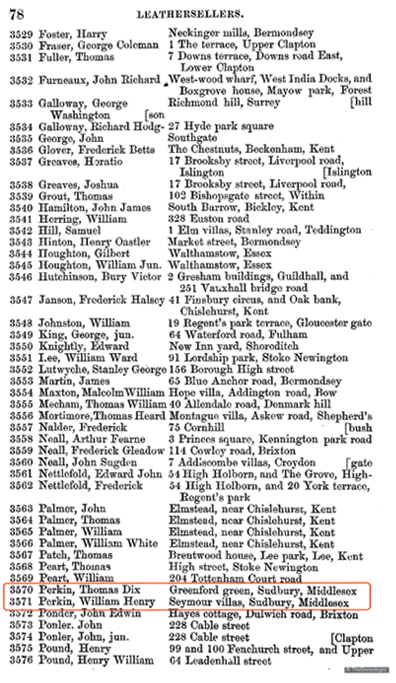

By using the poll books collection on TheGenealogist, we can also find William and Thomas Perkin as persons entitled to vote in the City of London as liverymen of the Worshipful Company of Leathersellers. Their membership of this livery company was as a result of their grandfather, Thomas Perkin, having been a leather worker who had come down to London from Yorkshire. Today the Leathersellers Company website explains that at their headquarters ‘the stair carpet is coloured mauve. This, together with purple walls on the floor below, acts as a reminder that one of the most famous Masters of the Company was Sir William Perkin’.

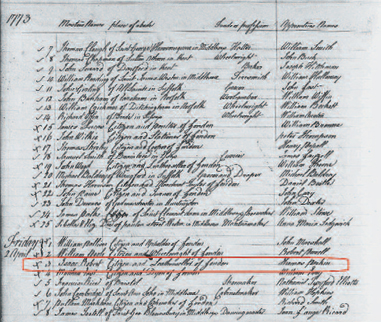

A search of the occupational records on TheGenealogist includes apprenticeship records taken from the Board of Stamps: Apprenticeship Books at The National Archives (series IR 1). We are able to find a Thomas Perkin apprenticed to Isaac Robert, citizen and leatherseller of London, indentured in 1772 for seven years, with the duty paid on 2 April 1773.

From a Yorkshireman, seeking his fortune in London as an apprentice leatherworker, to his son establishing a prosperous carpentry/builders business in the East End this is a story of a family that sought out opportunity when it presented itself. The Perkins then moved into new pastures when one of their number, while still a teenaged student, recognised the potential of the byproduct of his failed coal-tar experiment and the Perkin family entered into the chemical dyeing industry. From this base the next generation rose up through the academic world by becoming professors of chemistry. Professors William Perkin and Arthur Perkin also followed their father, Sir William, to be awarded Fellowships of the Royal Society (FRS), an honour given only to those who had made a substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge. By using the records on TheGenealogist we have been able to trace a family as over the generations they climbed up through society.

Frederick Mollwo Perkin, a consulting chemist in 1921 directory

The Register of Persons Entitled to Vote in the City of London 1877 on TheGenealogist

Altered apportionment Tithe map from 1909 on TheGenealogist

1773 IR1 Board of Stamps: Apprenticeship Books on TheGenealogist courtesy of The National Archives